about eddie brown

Additional Information

About Eddie Brown & Howard Blume (and we've added two articles about Charlotte Blume, Howard's mother, who died May 11, 2016)

(Whenever possible, we've included links to the original article. We encourage you to read these articles by linking to the publication and thereby helping to support print journalism.)

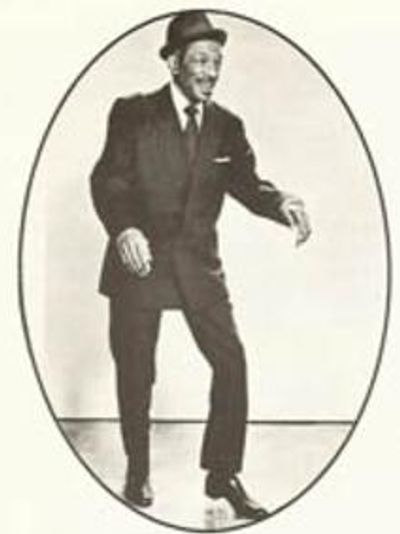

The Eddie Brown class is so named because it was originated by rhythm tap dancer Eddie Brown (pictured at right), who taught this group of students until his death in 1992. After that, class members requested that Blume continue teaching the class, and he has done so, with Brown's students staying on.

Blume's day job has, for years, been journalism. In 1992, he was working at the L.A. Times and had the opportunity to write a feature on Eddie Brown, who was ailing but still well enough to attend a performance in his honor.

Brown was a marvelous improviser, meaning he could invent taps to music as he performed, much the way a jazz musician improvises off a melody. But Brown could never remember the steps he invented while performing—or even in class. That became Blume's job. Brown would do a step and Blume would see it and perform it back to him. That allowed Brown or Blume to teach the step to the rest of the class and gradually put together routines. Blume also had the role of setting the routines to music, editing them to fit and adding beginnings, endings and transitions as necessary.

In the ongoing class, Blume revives Eddie Brown routines, while also mixing in his own and those of other dance masters with whom he had studied.

Below are six news articles and a video about Eddie Brown, Howard Blume and/or the Rhythm Tap Class. (Blume's articles on Tap Dancing can be found on the ARTICLES page. After these are the articles about Charlotte Blume):

Spectrum TV feature on Howard Blume from Dec. 2019: Click Here

Article about Blume's Rhythm Tap Class by Erin Aubry Kaplan (article not available online, read it below)

Blume's 1992 profile of Brown

Brown's obituary, written by Blume (There's some overlap with the profile.)

An article about a memorial performance, by Ed Boyer

A column musing about the Eddie Brown class by Erin Aubry Kaplan

A 2022 interview with Blume about combining careers in tap and journalism by Amaris Castillo, for the media news site poynter.org.

Tap dancer Eddie Brown

Articles about eddie, Howard or the class

Article 1 of 6

L.A. Weekly

Oct. 8, 2004

Best Rhythm Method

(For 2004 “Best of L.A.” edition)

By Erin Aubry Kaplan

I had been away from tap dancing for many years before I went to observe, at the suggestion of a co-worker, a class that gathered on Saturday mornings somewhere on the Westside. I was a bit intimidated by the location -- I envisioned snooty ballet types with perfect thighs and toe points that suggested years of classical training, the very antithesis of tap.

I needn't have worried.

The "studio" turned out to be a dim, somewhat nondescript restaurant near Pico and Exposition called Cafe Danssa, a sweaty Brazilian or Greek dance club on most weekend nights.

Its milder alter ego was this Saturday morning tap class made up entirely of women, most of them very friendly and decidedly older than me; though I hadn't put on tap shoes in more than 10 years, I was confident I could keep up by sheer dint of youth and flexibility.

Wrong.

While the group moved easily through a repertoire of routines and rhythmically intricate combinations by the late, great hoofer Eddie Brown, I shuffled haplessly about; by the end of the 90 minutes, I was nearly shedding green tears of frustration and envy.

I fled.

But I was also determined to come back and show the class that I had at least as much mettle as they did, dammit. And being black, I certainly had these wannabes beat on the rhythm gene, right?

Uh-huh.

After seven years of coming back, I'm entirely unsure of the answer on either count, but it doesn't matter; I've gone from green to mellow yellow. Learning the sole-ful legacy of Eddie Brown has been well worth the time, and the camaraderie of my fellow students runs a close second.

The teacher's not bad either, a bookish type who's a study in patience and meticulousness that seems to run counter to the spontaneous clatter of the art form. But then he puts on the music and dances alone, and you just say, Uh-huh. The famously unforgiving Eddie would have approved.

(Full disclosure: Said teacher is Weekly staff writer/editor Howard Blume.)

(Website editor's note: The tap class met at Café Danssa from about 1996 through Feb. 2007—when the much-beloved Café Danssa closed. Classes are now held in Silver Lake at the home studio of Howard Blume. Also, Blume currently works as a staff writer for the L.A. Times; he was a Weekly staffer from 1994 through 2004.)

Erin Aubry Kaplan is the dancer on the left.

ARTICLES ABOUT EDDIE, HOWARD OR THE CLASS

Article 2 of 6

HONORING THE GENIUS OF EDDIE BROWN;

DANCE: FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES PLAN A BENEFIT FOR THE UNDERRECOGNIZED GENIUS OF TAP.

BYLINE: By HOWARD BLUME, TIMES STAFF WRITER

SECTION: Calendar; Part F; Page 4; Column 1; Entertainment Desk

It's OK if you know, but don't tell tap master Eddie Brown about the foot-stomping, rhythm-dancing benefit show planned in his honor Sunday at the Morgan-Wixson Theatre in Santa Monica.

The 73-year-old dancer doesn't usually read The Times so it's safe to report that the show will feature plenty of tap colleagues who care about Brown, including Fayard Nicholas of the Nicholas Brothers and Fred Strickler for starters and groups including Rhapsody in Taps and the Jazz Tap Ensemble.

The guest of honor will be Brown. The wispy, soft-spoken man is less known than many who will pay him homage. But to a small, dispersed community of tappers, Brown is a guru of rhythm improvisation, the art of creating complex tap rhythms spontaneously. Brown, who is battling cancer, has long been a vital link to one of the most interesting and intelligent styles of this American dance form.

Organizers hope the benefit will give long overdue recognition to Brown, who lacks not only widespread fame, but material markers by which lives are measured. The Omaha native has no wife, no kids. His rented bachelor apartment is in a timeworn building a few blocks south of the bad part of Hollywood Boulevard, where Brown buys $8 shoes and splashy polyester shirts.

To see him cross a street or stage, it's hard at first to imagine that this man once was a protege of Bill (Bojangles) Robinson, the spectacular, influential dancer who achieved mainstream recognition as Shirley Temple's aged dancing partner.

According to legend, Robinson discovered the teen-age Brown when his troupe was passing through Omaha. The 16-year-old entered a dance contest Robinson had organized.

Robinson asked Brown what number he planned to do.

"The same one that you do," Brown replied.

"And what music do you want?"

"The same music that you use," came the answer.

Brown had memorized "Doin' the New Low-Down," one of his idol's routines, by listening to the taps, scrapes, digs and shuffles on a scratchy 78. Then Brown went to a movie house to watch Robinson on film and match the sounds to the style.

Brown's cheekiness was a risk. Robinson jealously guarded his material. He was reputed to brandish pistols at dancers who stole his steps.

And Brown had stolen them perfectly.

Instead of losing his temper, Robinson offered Brown a job.

Brown ran away to New York City when his parents wouldn't let him join Robinson's troupe. He eventually toured China with Robinson before World War II. Brown left Robinson's company in the 1930s to become a solo performer, mostly in the San Francisco area.

Nowadays, Brown looks as if he would have trouble vaulting an anthill. Even before his recent illness began to sap his energy, he stepped gingerly, slowly, sometimes stiffly.

Start the music, though -- or ask him to move to the song in his head -- and his toes stirred in his shoes. The feet started to glide across the floor. Brown's face remained expressionless, and the arms dangled loosely. But metal rapped against floor faster than a woodpecker's beak to maple -- and with a metronome's precision.

Brown's genius is his ability to release a firestorm of creativity into his short-term memory, and translate that instantly to his feet.

Most tappers who improvise steps are not truly starting from scratch. Rather, they string together patterns from previously memorized routines.

Brown, however, strolls onstage or into class with little or no plan. And no conscious memory of the steps he created last year, last week or five minutes ago. That's the way he's been as long as his students can remember.

It's as though his incomparable inventiveness developed at the expense of other attributes, such as an acute memory. Like a hitter who sacrifices batting average to swing for the fences, Brown's choice is a trade-off.

Brown's part of the bargain includes a few minutes of motion in which the 5-foot-7-inch, 110-pound dancer can practically improvise youth from old age, laying out moves that would wind an Olympian or confound a lesser dancer.

Off the dance floor, it's been harder to improvise through difficult times. After World War II, no one wanted nightclub tappers, no matter how good they were. He taught himself to play the piano and got by as a musician when he had to.

Friends say he fell deeply in love at one point and was crushed when the woman left him. Some speculate that maybe Brown's heavy drinking caused the breakup -- or the breakup his drinking. Sometimes his idea of grocery shopping was buying a carton of Pall Mall Gold 100's and a fifth of Korbel brandy.

He's never lost his romantic's heart. Old movies never fail to bring a smile to his face and a tear to his eye when the hero finally gets the girl.

Just six months ago, he talked of getting married someday when his career is better established.

Mostly, he reserves his passion for teaching and performing.

"I have this much time for mortal endeavors," Brown told a friend once as he held two fingers about an inch apart. Then he extended his arms as wide as they would go. "This much is about my dancing."

His turning point as a teacher came 20 years ago, when some young dancers spotted Brown stealing scenes in a San Francisco musical review. They begged to study with him.

Brown soon developed a following, and took his fortunes to Los Angeles about 10 years ago. The reputation of "Schoolboy Eddie," as other veteran black dancers called him, began to spread from coast to coast among the tap-dancing elite.

"You can't create the things he does without having a great mind as well as a great ear and a good sense of time," said Mike Mailloux, an Arizona dance instructor who studied extensively with Brown. "I found the soul of my dancing after working with Eddie."

Other disciples praise his generosity.

"He's never held back anything he knows," said Babs Yohai-Rifken, a San Franciso-area teacher. "There aren't many people willing to share all their stuff."

A cadre of admirers will do almost anything to keep Brown teaching and surviving. Almost everyone has a role in a Saturday class he teaches in a rent-by-the-hour studio in downtown Los Angeles.

Virginia Conti, 74, faithfully keeps the books and collects the class fees for him, as she has done for a decade. Lillian Hill sometimes brings the record player, and sometimes brings Conti or Brown. Constance Danielson writes down steps, so they won't be forgotten from week to week. Carolyn Clarke helps organize some of Brown's performances. Debra Bray takes Brown to the doctor and helps him buy groceries.

He rewards them with a laugh that bounces off the walls when he's pleased with a step they've learned. "That's outta sight," he tells them. "Ain't nobody doin' what you're doin'."

A friend once asked Brown after a class if he had any regrets about the way his life had gone. Brown paused thoughtfully, then carefully pulled off his shoes as he replied.

"No, not really," he said. "None that's worth remembering."

The Salute to Eddie Brown concert will be 7 p.m. Sunday at the Morgan-Wixson Theatre, 2627 Pico Blvd., Santa Monica. Tickets are $15 for general admission.

ARTICLES ABOUT EDDIE, HOWARD OR THE CLASS

Article 3 of 6

December 30, 1992, Wednesday, Home Edition

EDDIE BROWN, RHYTHM TAP MASTER, DIES

BYLINE: By HOWARD BLUME, TIMES STAFF WRITER

SECTION: Metro; Part B; Page 1; Column 2; Metro Desk

Eddie Brown, a master of rhythm tap improvisation who schooled a younger generation of dancers, died Monday at a convalescent hospital in Los Angeles. He was 74 and had been battling cancer.

Brown overcame poverty and alcoholism as well as decades of obscurity to win acclaim among tap-dancers as a dancer and teacher.

"He was one of the greatest exponents of rhythm tap," said Rusty E. Frank, a tap historian who compiled an oral history of tap-dancing. "His rhythms were so musical and so complex that it was a thrill for people to watch and listen to him. He went far beyond what most tap-dancers even tried to grasp."

Brown rarely performed routines. Instead, he mesmerized audiences with a no-nonsense, almost expressionless dancing style that featured genuine improvisation. When the band played, he would spontaneously weave delicately intricate, rhythmically diverse combinations.

"You can compare rhythm tap to jazz music," Frank said. "As far as the resurgence of tap goes, he is one of the key figures on the West Coast. Since the 1970s, he has been available, willing and anxious to teach the next generation.

"In New York they had Honi Coles. In California, it was Eddie Brown. He kept rhythm tap alive."

Some believe that Brown made his greatest contribution by passing on the rapid-fire, close-to-the-floor, musically complex style that is rhythm tap.

"He wasn't ever afraid to give away any of his best steps because his best steps were constantly coming," said Babs Yohai-Rifken, a San Francisco rhythm tapper and dance instructor.

Brown was born in Omaha, one of 14 children in a family that included musicians, singers and dancers. His most important early dance teacher was an uncle who would rap Brown's ankles with a stick if he got steps wrong.

Brown also learned tap on the streets. In his day, teen-agers met on street corners to show off dance steps and learn from each other.

According to legend, famed tapper Bill (Bojangles) Robinson discovered the 16-year-old Brown during a tour in Omaha. Robinson asked Brown what number he planned to do.

"The same one that you do," Brown said.

"And what music do you want?"

"The same music that you use," came the answer.

Brown had memorized "Doin' the New Lowdown," one of his idol's routines, by listening to the taps, scrapes, digs and shuffles on a scratchy recording. Then Brown went to a movie house to watch Robinson on film and match the sounds to the style.

The young dancer's cheekiness was a risk because Robinson was reputed to brandish pistols at dancers who had stolen his steps.

And Brown had stolen them perfectly.

But instead of losing his temper, Robinson offered the boy a job.

Brown ran away to New York City when his parents would not let him join Robinson's troupe. He eventually toured China with Robinson before World War II but left the troupe in the 1930s to become a solo performer, primarily in San Francisco.

After World War II, the market for tap dancers dried up and Brown taught himself to play the piano, getting by as a musician.

Brown said that despite those lean years he never considered giving up his dance. "I have this much time for mortal endeavors," Brown told a friend once as he held two fingers about an inch apart. Then he extended his arms as wide as they would go. "This much is about my dancing."

He emerged from the shadows in San Francisco in the mid-1970s, when he performed as the lead tap dancer in "Evolution of the Blues," a music and dance variety show that traced the birth and development of blues music and featured noted black entertainers.

His performances inspired dancers to seek him out for lessons, and from that time, Brown's class became a required stop for hundreds of students.

He moved to Los Angeles in 1982, where he continued teaching. Periodically, he participated in performance tours and dance conventions around the world, where he was typically a lead attraction.

Honors in recent years included two choreographer fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and a star on San Francisco's Walk of Fame. This year, local tappers organized two shows in his honor. The most recent, on July 26 at the Morgan-Wixson Theatre in Santa Monica, drew an overflow crowd.

Brown outlived his siblings, said Emelda Brown, a niece. A memorial is pending.

ARTICLES ABOUT EDDIE, HOWARD OR THE CLASS

Article 4 of 6

January 7, 1993, Thursday, Home Edition

SAVING THE LAST DANCE;

FRIENDS HONOR LEGACY OF TAP MASTER AND TEACHER EDDIE BROWN

BYLINE: By EDWARD J. BOYER, TIMES STAFF WRITER

SECTION: Metro; Part B; Page 1; Column 2; Metro Desk

Old masters and young phenoms brought their tap shoes and memories to Los Angeles' Ebony Showcase Theater on Wednesday to do "the Eddie Brown," a dance chorus named for the generous genius who died of cancer last week at 74.

They remembered Brown, a master of rhythm tap improvisation, as an innovator who -- unlike most accomplished dancers -- was more than willing to teach them each new step as it came whirling from his imagination.

"He wanted to give you his best steps because he would forget it in five minutes anyway," one student said. "The only way to preserve an Eddie Brown step was in somebody else's memory."

Some tap dancers could do eight bars, or maybe 16, but Brown "could do dance after dance after dance, and it just rolled out -- this beautiful rhythm," said Los Angeles dancer Fred Strickler.

Strickler once asked Brown if he ever got lost in the midst of all those complex rhythms he created.

"I get lost all the time," Brown said. "Sometimes I didn't know how I would get out. But I just trusted my feet."

Brown began trusting his feet on the streets of Omaha where he was born and began dancing. At 16 he met "Mr. Bojangles" himself, Bill Robinson, and brashly demonstrated a pilfered Robinson routine. He later toured China with Robinson before launching a solo career in the 1930s.

After World War II, the demand for tap dancers virtually disappeared, so Brown taught himself piano and scraped by as a musician. But even leaner years were to come, and Brown waged twin battles against poverty and alcohol.

He had come from a generation of unappreciated geniuses, black performers who toiled for the sheer love of their craft and art because they were not offered the contracts that might have come their way had they been white.

"The steps you saw from Eddie Brown were not merely dance steps -- they were the sounds of survival," said Paul Kennedy, master of ceremonies at Wednesday's memorial. "A lot of times he would do a step in hopes of getting a sandwich -- or a job. Those moves were very, very serious."

Kennedy, who teaches tap at his sister Arlene's Universal Dance Designs studio in Los Angeles, said Brown and many other great black dancers "knew they were good. They got jobs, but they didn't get what they should have for being as good as they were."

Eventually, the attention came with the resurgence of tap, Kennedy said, and it came from many of the people in the theater on Washington Boulevard on Wednesday.

In the mid-1970s, Brown resurfaced as lead tap dancer in "Evolution of the Blues," a San Francisco production that featured black entertainers.

He may have found fame elusive, but his genius was abiding. Soon the word was out about this man whose style was described as dancing "close to the floor" and who did things with his heels that other tap dancers found astonishing.

Tap historian Rusty E. Frank, who met Brown during those San Francisco years, said: "His complex rhythms were his greatest contribution to tap. He was willing to sit down with kids and pass on his material. A lot of old-time dancers didn't want you to use their routines."

Brown moved to Los Angeles in 1982, continuing to teach, perform and occasionally tour.

"He had a unique style," said Arthur Duncan, a tap soloist on the Lawrence Welk Show for 20 years. "He was an exponent of close rhythm dancing -- rhythmic patterns as opposed to leaps and jumps."

Dance teacher Arlene Kennedy said Brown described everything he did as "scientific rhythm."

"He said he found how he could cut the tempo of the music in half and double the rhythm of the steps," she said.

Actor Nick Stewart, 81, a remarkably agile tap artist who runs the Ebony Showcase, described Brown as "just a master dancer. It was a thrill to watch him. Just makes chills go through you."

His friends remembered his personal style as much as his dancing on Wednesday, fondly recalling his Stetson hat, his glasses falling down across his nose, his enthusiastic greetings and the accolade he extended when someone correctly performed a step: "Outta sight."

As he battled the cancer that would take his life, Brown insisted on teaching his classes on Saturday mornings, and he depended on his students to keep the sessions organized and running.

"We just loved him," Lillian Hill, one of his students, said Wednesday. "He was a terrific man. He had it to give and we took."

ARTICLES ABOUT EDDIE, HOWARD OR THE CLASS

Article 5 of 6

February 1, 2006 Wednesday

Home Edition

ERIN AUBRY KAPLAN;

BYLINE: ERIN AUBRY KAPLAN

SECTION: CALIFORNIA; Metro; Editorial Pages Desk ; Part B; Pg. 11

"Stepping back to see the magic of tap; It took a long time to learn that the dance form was more than a kick."

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED tap the way a lot of kids in my neighborhood did in the early '70s: through classes offered at a local park. Though great fun -- who doesn't enjoy making clattering noises with their shoes for hours at a stretch? -- tap felt to me like the less-cultured cousin of ballet, a default dance form for those whose feet could not achieve a proper turnout or go up on pointe (my feet could do neither, of course).

I eventually came to appreciate the subtleties of tap, its exacting rhythms and intimate connections to the jazz it was set to, its surprising sense of narrative. Yet I didn't quite respect it in the way I respected ballet. Tap was a blast, and therein lay the problem: It was too loose, too easily divined, too eager to please.

Put another way, it was too black. Ballet was lovely, reserved, straight-backed, authoritative -- it was unquestionably white. Politically unformed though I was at 8, I sensed that if I could master ballet instead of tap, I would be in a much better position to succeed in life. Tap was on the ground where I already was. Ballet was up in the clouds, and I concluded that while people on the ground commented on the world -- rhythmically, loudly, passionately -- those higher up actually ran it.

Tap offered spirit to all; ballet offered power to a chosen few. Sure, my classmates and I got hearty applause for performing in silver bowlers and matching cuffs. But the hush that settled over an audience when the advanced ballet groups took the stage and hit their grand jetes was gold.

So I dropped tap and didn't return to it until I was about 20, when I was actually thinking about pursuing a career in musical theater. By then I had developed a fairly ambivalent take on tap.

On the one hand, I saw it as a precious American art form that was historically undervalued because it was black. On the other hand, I was embarrassed by its close association with vaudeville and minstrelsy and the relentless good-time grinning of tap dancers, even masters such as Bill Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers.

Tap wasn't serious , which is what I aspired to be. I studied a bit more before leaving it alone -- again.

It wasn't until 1997 that I came to terms with tap. I discovered a class on the Westside started by Eddie Brown, a legendary black tapper I'd never heard of who'd fallen into obscurity and near-poverty; he taught classes to make money and to keep himself dancing.

Eddie was a rhythm tapper, meaning his style was grounded in improvisation and mid-tempo, complex beats. He wanted to be taken seriously too, and from what I could gather (he died of cancer before I started taking his class) he spent his life proving he was master of an art form that he helped make unique.

As a student of Eddie's routines, I quickly realized that he wasn't just commenting, he was creating -- much as George Balanchine created ballets. Nor was his stuff easy. Perfecting a typical Eddie combination required more stamina and muscle control than perfecting a plie or jete. I sometimes got so frustrated I stormed out of class early, vowing once again to never return to tap.

But the magic of the art form -- not its drawback, as I once assumed -- is its accessibility, its standing invitation for anyone with hard-soled shoes and a minimal sense of rhythm to get up and give it a try. Only after you get up do you discover that discipline is mandatory and that exceptional tappers, like exceptional ballet dancers, are rarities.

I'm not one of them. I am, however, a true believer in the power of tap. He hardly ran the world, but Eddie Brown had power; so did Fayard Nicholas, the older half of the Nicholas Brothers tap duo who died last week at the age of 91. Fayard was as bubbly and upbeat about his experience in show business as Eddie was unresolved and slightly embittered. Yet both endured racism, which contoured and curtailed their careers, and both prevailed.

Part of what makes tap black, I came to realize, is its extraordinary legacy of perseverance, the ability to exude lightness and grace under a kind of pressure I can only imagine. It's a legacy I'm still working to live up to, one step at a time.

ARTICLES ABOUT EDDIE, HOWARD OR THE CLASS

Article 6 of 6

Poynter.org

April 29, 2022

"Los Angeles Times reporter Howard Blume on his lifelong love for tap dancing:

'Hotel Tapifornia' — his first show since the pandemic — had its opening last weekend. The final show is this Sunday."

Los Angeles Times staff writer Howard Blume returned to the stage last weekend. It wasn’t for another investigative reporting accolade, but rather for a tap dance show he choreographed and pieced together. Blume, who comes from talented parents, has had a lifelong love for tap dance. And like other journalists, he’s managed to maintain his journalism career and carve out time for his passion. He covers education for the Times, teaches through Tap Dance with Howard and also choreographs dances.

Blume celebrated the opening weekend of “Hotel Tapifornia” with his performance group, the Tapitalists, last Saturday and Sunday. It’s their first show since the pandemic began. It continues this weekend through Sunday. Before his opening weekend, we spoke with Blume about his love for tap dance, journalism and how both coexist in his life.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

First, I’d like to congratulate you on your upcoming show, “Hotel Tapifornia.” How do you feel?

I feel pretty good. I’m at the stage of the show where I ask myself, “Why do I do this?” Because it practically kills me with everything that I’m putting together in the show. I hope people enjoy it. It’s a fun show and probably has more of a plot than some of our other shows, although it varies. Every show is completely different from the previous show — different music, different choreography, different approach — so that people who come to our shows more than once will get a very different experience each time.

The name of the show feels so familiar. Are you a fan of the Eagles, the band?

Yes. I wouldn’t say they’re my absolute favorite, but there are a couple of songs that I really like. One of the interesting things about the show is that we present an eclectic mix of music for choreography. In this show, we actually have a live jazz pianist to spice things up a bit, but most of the choreography is an eclectic mix of music that includes Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Artie Shaw, who was a well known big bandleader, the Eagles, and also John Williams, the classical music and soundtrack composer. So that’s an interesting mix of music.

In these shows, we let people hear a variety of music, and also see how tap can be set to that music. The core of our tap is rhythm tap, which may or may not make sense to some of your readers but it’s similar in its heritage to jazz music and it owes a major debt to Black artists in the early and mid-part of the 20th century.

You’re an award-winning education reporter for the Los Angeles Times. How did you manage to put together a tap dance show around your job? I’m a former newspaper reporter and I know how grueling that job is.

I’ve learned over the years to be very efficient, and I don’t clean my house very often.

Oh, no. I understand. Is this your first show since the pandemic began?

It is. I have a side business — a dance school that specializes in tap dancing. In order to keep my time-consuming job at the paper going — and it is very time-consuming, as you alluded to — I’ve kind of automated the signup system for my classes as much as possible. People sign up online, and I just try to limit myself as much as possible to teaching and choreographing.

It takes some time to put a show together. Even if there had been a pandemic, I might not have produced a show any sooner than I’m producing. … We’ve actually been in masks since we moved indoors. I have a vaccine requirement for the tappers. For the show, I’m requiring all the patrons who show up to wear masks. And if they don’t have one, we will happily provide one. It’s just an odd time to put on a show.

In recent years, we’ve had topical references, sometimes satirical, to current events. That is somewhat true in this show. People who see it will recognize, in a gently satirical way, some nods at current events.

So like COVID humor, if that’s such a thing?

Well, not so much COVID humor. In this show, we poke some fun at people who oppose things they don’t understand, who oppose science and who present with anger to the world. For example, these extremists talk tough generally by making harsh, guttural noises, and parade around with signs such as “Ban Critical Space Theory,” “Annoy all immigrants,” and, “I’m angry. I don’t know why.” You can use your imagination to figure out what we’re poking fun at there.

I read that, in your show, a weary traveler stumbles on a dance oasis in the remote California desert, an area patrolled by a police force that has never detected this mysterious resort, where it seems everyone has a past. There’s a question of whether Hotel Tapifornia is real, or good, or bad. What was the inspiration behind this?

This is going to sound very nonserious, but to be honest, me and my friends and relatives are always making puns with the word “tap” in them. I have a long list of potential show titles that involve a pun using the word “tap.” Even though that’s a game we play, once I settle on something, I have to turn it into a serious (show), in the sense of quality. Something that makes sense and holds together in a narrative way.

“Hotel Tapifornia” came up on the list, and I just decided I like that name. Once I had the name and idea for the show, I used some of the dances that I’ve been working on over a two-year period, and then I put the plot together. The plot will drive the creation of some of the additional dances.

That’s incredible that this kind of originated from a pun. Do you have any favorite tap puns?

You caught me at 8:13 in the morning, when my brain is not quite as sharp as it should be. I thought about doing a show about various aspects of romance called “Love Taps.” That was one.

Can I just say, that is very punny.

Thank you. Thank you. I’ll pull up out my list and send you a couple.

I want to take it way back. What’s your earliest memory of tap dancing?

I grew up in a dance school operated by my mother, and so I don’t remember not tapping. Apparently, according to a report, I started when I was 4, and then I quit for a year. So that means my 5-year-old year was without tap.

Oh no [laughs].

That was a rough year all around for me. I’m lucky I ever made it out of kindergarten. On a side note, my only strength in kindergarten was that I was the best napper in class. But I had trouble tying my shoes. I still have a little trouble tying my shoes. It was a rough year.

Kindergarten’s tough.

But at 6, I resumed tap. My rebellion was actually tap because my mother was a ballerina and a ballet teacher, and she probably would have much preferred for me to pursue ballet. But I rebelled by being more interested in tap instead.

Your mother, Charlotte Blume, was a ballerina, and I read that she taught for decades from her studio in North Carolina. What can you tell me about her influence on your dance journey?

She made sure that I had good training when she saw that I had an interest in tap. She had a tap teacher, but she did not stop with her. … She made sure that I got to New York and Los Angeles to study advanced tap with people who are no longer around.

She could be a very difficult person, but she had a lot of integrity and believed in high standards. She was very committed to her local community. She is legendary in that region in North Carolina because she actually brought high-quality dance to the region. … She was like a big city talent in a small city.

Both my parents, in their own way, were very active in the civil rights movement. My mother refused to segregate her classes when she opened her dance school in the late 1950s. As a result, for close to two years, she had only Black students because the white students were boycotting her studio. But it broke down because everybody realized that they wanted to learn how to dance and there was only one studio in town that was offering this caliber of lessons.

What about your father, Dave Blume? I read about his life as a jazz musician and composer. Did that have an influence on your interest in the arts as well?

It did. Because if you think about it, tap dancing is a combination of the dance arts, but it’s also very musical and jazz-oriented. His musicality, his range of musical tastes, and his own musical ability were influential as well. Both my parents were very talented. They were not suited to remain together, and they both went on to better marriages eventually. But they were both extremely talented. My father was a fine jazz musician. I did one show a few years ago that was based on his jazz compositions and his arrangements that I did not discover until after he died.

Thanks so much for sharing that. I saw that you began teaching tap at age 14, at your mother’s dance studio. What was it like to teach so young?

The teacher at the time — who was a wonderful lady and a great tapper — was getting older and struggling with certain aspects. I would be constantly helping her, which she appreciated, and she gradually turned the job over to me. It just felt normal because that was my life. If you grew up in a dance studio, you dance and then you teach. It didn’t feel strange at all. Teaching and choreographing have always been my focus.

I’ve performed a fair amount, but I just didn’t pursue a career in performing because that seemed a little sketchy to me. I preferred the solidity of a job in journalism. Little did I know what journalism would become. But at the time, it seemed that journalism was a career that offered more stability and I could still continue to teach and do it on my own terms.

I want to talk a little bit just about these past two years as a journalist. As a newspaper reporter, you’re on the daily grind. And being that we’re still in a pandemic, can you describe how these past two years have been for you as a journalist covering education?

It has been a challenging two years in that the education news and the pandemic news, in general, has never stopped. It felt a little that way during the Trump administration, where it seemed the news never stopped and there’s always something of momentous importance to write about. Of course, post-pandemic, it seems a little that way with the invasion of Ukraine and other things, but the pandemic was certainly a challenging time for education reporters.

The one thing I actually appreciated about this period was that I did not have to go into the office. I missed seeing my colleagues and interacting with them, because journalists are a very witty group of people and fun to be around, but I did not miss the commute. The truth is, the time that I used to spend driving, I spent working instead — so it was a very efficient year …

I think teachers and students have had it harder in a way, because there’s just been so much stress on teachers. They did not ask to do a job in which they had to work online all the time and not have direct interaction with people, which was the case for a while. They did not ask for a job in which they might have to put their life on the line, based on what we knew at the time. And students have been so harmed in their intellectual and social development, and that’s been difficult for families, too. Reporting stories has sometimes been a challenge because you meet people and you couldn’t go into their houses to talk with them, or take their picture. You would have to meet outside, you couldn’t see their faces behind the mask. So it’s been challenging, and most everybody has been working too hard. Not just me. I’m not a special case in any way, but it has been difficult.

And did you keep on dancing over these past two years? I imagine you did.

I did. It helps to have a dance studio [laughs] because I can go there and practice or work out and choreography all night, if I want to.

How do you juggle your journalism, work and dancing? How do you do it generally?

Generally, I tell my editor what my schedule is and she tries her darndest not to interrupt me during the relatively few hours a week that I’m teaching classes. She tries, and when she does interrupt me, I know that it’s something important. And my students understand that I have this other job. Once they are aware of this, they accept these brief interruptions and they keep themselves occupied just fine. I do most of my teaching on weekends, so if they need me to work in extra shifts at the paper, I asked them to schedule me for Saturday night or Sunday night because I teach during the days on Saturday and Sunday. And they’re willing to do that.

Are there any parallels between reporting and tap dancing? I know that might be a strange question.

There are, in a way. Both involve a fair amount of stamina and there’s an intellectual component to both, which I like, and a creative component to both. They complement each other fairly well, as long as they don’t kill you. The journalism work exercises one part of my brain, and tap and the physicality of tap exercise another part of the brain. It also gives me an opportunity to be an employee. I’m perfectly good being an employee. And an opportunity to be in charge of my own thing, which also has its benefits.

How has tapping informed your journalism? Or has journalism informed your tapping?

I think it goes both ways. I think being a tap teacher, and having been one for decades, gives me an understanding of what teaching is about — including dealing with students of different ability levels, motivations and backgrounds, and trying to make the class work for all of them, which is what teachers try to do every day. I think that has helped a lot. In terms of journalism helping tap, it just gives me a more sophisticated way of approaching the world as an artist. There are some artists who are very talented in their craft, but not that well-informed about the world, or about issues in the world. You don’t have to be, but if you are, it can lend an element of depth to the way that you approach your art.

Do you find you approach either one differently because of your familiarity with the other?

It also helps to be able to write about tap. On my website, I put some explanations about tap, I put some articles I’ve written about tap and tappers. My research and journalism skills have helped me become something of a historian about tap. There are some really talented people who’ve written books about tap, including a journalist in New York who’s written what I consider the best history to date — his name is Brian Seibert. When I used to have a radio show, I actually interviewed him for the radio show because I thought his work was so high quality. But I think part of what I’m doing in tap is keeping a tradition and history alive. It’s been important to me to study that tradition and to use my skills as a journalist, both to research that tradition and to write about that tradition.

Articles about Charlotte Blume

Article 1 of 2

Fayetteville Observer

Fayetteville, North Carolina

May 11, 2016

Charlotte Blume, the princess of pirouette, succumbs to cancer

By Bill Kirby Jr., staff writer

Charlotte Blume - who taught ballet, tap and dance to young women by the thousands - died Wednesday morning at a hospice care in Smithfield after a brief battle with pancreatic cancer.

She was 85.

"She made it very clear that she wants the studio and the ballet company to continue," her son, Howard Blume, said about the Charlotte Blume School of Dance in Haymount, which has its spring recital scheduled in 25 days at the Crown Theatre. "While in the hospital, she worked out a letter to studio families with the message."The message was Charlotte Blume personified.

"The show must go on."

Mr. Blume said that in keeping with his mother's final wish, the recital will be staged at 2:30 p.m. on June 5, to be followed by a Celebration of Life that will include a video tribute of Mrs. Blume instructing students and her dancing to a performance of "Giselle.''

Mrs. Blume's annual productions of the "Nutcracker" and "Swan Lake" have become community traditions from the local stage to the North Carolina State Ballet, and she became the community's princess of pirouette and diva of dance.

And a dance instructor who never said no to a student, no matter the color of their skin, who came to her school with the desire and the dream of dance.

"I enjoyed performing and still like performing," Mrs. Blume said prior to her March 25, 2015, induction into The Fayetteville Music Hall of Fame. "But teaching is special because I am able to give something to others."

Students were the fruits of her dance instructional labors, and their talents and successes were not lost on Mrs. Blume, who was known as a strict disciplinarian when it came to bringing out the best in her students.

"My students were wonderful," she said last year.

But she demanded their best and she insisted on nothing less.

"What dance does for children is that it teaches them self-awareness," she said. "They learn to use their bodies in a graceful manner and how to carry themselves. I try to encourage them and hope they have high expectations, and as they aspire and achieve, I take great satisfaction to see them succeed."

Born April 12, 1931, the oldest of three daughters to Harry and Jenny Abrevaya, a trained dancer, in New York City, Mrs. Blume graduated from Northeastern University in 1954 with degrees in English and biology.

She began her dancing career under Harriet Hoctor, a star of the Ziegfeld Follies and a former partner of Fred Astaire.

She had a ballerina's characteristics - a small frame, long legs, feet that arched, and a conscious element of moving her arms like a swan.

She signed on later with the Water Follies, a traveling water and stage show.

Mrs. Blume came to this community a year later, when her husband was drafted into the Army and assigned to Fort Bragg.

She was a teacher at Person Street Elementary School from 1956 to 1958, and began teaching dance on Fort Bragg in 1957 after performing in USO shows on the military post.

She helped organize a dance recital for black students on May 8, 1957, at Seabrook Auditorium on the Fayetteville State University campus.

She opened her own studio in 1959 over a funeral home, and it was not without controversy.

"No one was going to tell her not to teach black students," Howard Blume, 55, said about his mother, who willingly accepted the daughter of a prominent black family as her first black student. "Or not to place them in the same classes as white students."

If you were a young woman with the desire to dance, Charlotte Blume was going to teach you.

Mrs. Blume was about dance, particularly the classical ballet.

By the early 1970s, as her legend as a dance instructor grew, Mrs. Blume took over the North Carolina State Ballet, moving its headquarters to Fayetteville, where she hired the ballet's lead dancers as teachers, too.

With the state ballet, Mrs. Blume directed the "Nutcracker,'' and played the role of the mother in the first act. In her production of "Swan Lake,'' she danced to the role of the Queen Mother.

Mrs. Blume retired from dancing in lead roles in the 1980s, but teaching remained her passion.

"I think I brought a sense of professional dance to Fayetteville," she said in 2015. "And I am proud of that. I enjoy what I do and will probably do it as long as I can."

Mrs. Blume was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in March.

But she never stopped instructing and overseeing her studio, including its business affairs.

"Wei Ni takes over as artistic director of the dance school and ballet company," Howard Blume said of his mother's final instructions. "Darlene Anderson will serve as business director. Sheila King Mitchell will remain on staff teaching ballet, tap and acrobatics. Other teachers also plan to remain and new, additional teachers are being interviewed."

Mrs. Blume slipped into a coma on Sunday at SECU Hospice House in Smithfield.

"Mom is near the end of this phase of her journey," her son said at the outset of this week.

On Wednesday, the studio was closed.

"It is with much sorrow and a heavy heart that our beloved Charlotte Blume has danced her last swan song with us," the Charlotte Blume School of Dance said on its Facebook page. "Her passing leaves a void in all of our hearts. Please keep her family and Dr. Midgley in your thoughts and prayers during these difficult times."

A graveside service is scheduled for 11 a.m. Friday at Memorial Cemetery, 1000 Fairground Road, in Dunn, followed by a 1 p.m. memorial service at First Presbyterian Church, 901 Park Ave., Dunn.

Mrs. Blume is survived by husband, Dr. John Midgley; children Leo Blume of Palo Alto, Calif., and son Ansel; Howard Blume of Los Angeles, and his wife, Martha, and their children Rebekah and Hannah; and Margot Rudell of San Francisco.

Staff writer Bill Kirby can be reached at kirbyb@fayobserver.com or 323-4848, ext. 486.

Charlotte Blume

Articles about Charlotte Blume

Article 2 of 2

Fayetteville Observer

Fayetteville, NC

June 6, 2016

Dance students pay homage to beloved instructor Charlotte Blume

By Monica Vendituoli Staff writer

Charlotte Blume Midgley's passion for dance pirouetted on in the form of her students at the Charlotte Blume School of Dance 2016 Spring Festival at the Crown Theatre on Sunday afternoon.

A few hours after the performance at 7 p.m., an audience gathered again at the Crown Theatre to celebrate the life of the renowned dance teacher.

Blume died May 11 at age 85 after a brief battle with pancreatic cancer. Charlotte's last name was Midgley, after her third husband, but she was best known professionally by the last name from her first marriage, Blume.

She began teaching dance on Fort Bragg in 1957 and opened her own studio in 1959. At one point, her studio had more than 1,200 students with branches in more than half a dozen cities, the festival program said.

While in the hospital, she sent out a message to her students and their families insisting that the spring festival continue as planned after she died.

"She insisted that the show must go on," Blume's son Howard Blume said. "She wanted the studio to continue, the ballet company to continue and she also wanted to keep her commitment to the dancers."

Blume's dedication to her dancers led many to remembering her as a second mother or aunt rather than just a dance teacher. When her dancers were asked what she meant to them, many began tearing up.

"Look at their eyes already," Dina Lewis, of Fayetteville, said after seeing some dancers start to cry about Blume.

Lewis has two daughters who dance for Blume's studio. She said she savored every minute that her children received lessons from Blume.

"She was the epitome of a classical ballet teacher that you would expect to find in New York, but she was here in little old Fayetteville," Lewis said.

Lewis' daughter Ella Lewis, who began training with Blume at the age of 4, said Blume made her the dancer she is today.

"She inspired me because she would just get up and teach at her age," Ella Lewis said.

Blume didn't just tell the dancers what to do, Dina Lewis added.

"She was doing pirouettes in December," Dina Lewis said.

Many of Blume's dancers said her generosity set her apart from the rest.

Massey Hill Classical High School senior Destiny Payer plans to attend the North Carolina School of the Arts and major in dance afterwards. Payer said she couldn't have done so without training under Blume.

Payer said Blume developed her talents despite her family's financial constraints.

"We never had a lot of money. Even though we couldn't pay for the classes, she still let me take classes," Payer said. "She would have my mom work for her to help pay stuff off."

Blume's father worked for her studio when she was growing up to afford classes for her in a similar fashion, Blume's son Howard Blume revealed during the celebration of his mother's life Sunday night.

Her children first showed a slideshow of their mother dancing during her earlier years. They also showed the short film "Building a Performance: Giselle, Act II" produced by Blume.

Former students and friends of Blume then took to the podium to express their admiration for her. More photos and videos from Blume's past as a performer followed. A clip from Blume's March 25, 2015, induction into the Fayetteville Music Hall of Fame came next.

"I enjoyed performing and still like performing," Blume said at the event, "But teaching is special because I am able to give something to others."

The ceremony ended with a special performance of "Farewell to a Dancer" choreographed by Wei Ni, the Charlotte Blume School of Dance and the North Carolina State Ballet.

The dance concluded with each performer placing a white flower on the ground next to a portrait of Blume.

Staff writer Monica Vendituoli can be reached atvendituolim@fayobserver.com or 486-3596.

Photo of Howard and Hannah on this page by Largo Richardson.